Devon Island, located in the High Arctic of Canada, is the world's largest uninhabited island, offering a glimpse into one of the most remote and harsh environments on Earth. The island's geography is stark and dramatic, characterized by polar deserts, vast ice caps, and rugged mountains, including the notable Haughton impact crater. This diverse landscape provides a unique setting for studying Earth's geology and comparative planetology. The island's terrain is mostly barren, with very little vegetation, reflecting the extreme conditions that prevail here.

The weather on Devon Island is predominantly cold and dry throughout the year, with long, harsh winters and short, cool summers. Temperatures can plunge below -40°C in the winter and rarely exceed 10°C in the summer. Precipitation is minimal, making the environment akin to a cold desert. These conditions contribute to the island's status as one of the closest terrestrial analogs to Mars, making it an invaluable site for scientific research and simulation exercises for future Mars exploration. The wilderness of Devon Island is both desolate and beautiful, offering a serene yet austere landscape that challenges the resilience of life and human exploration. This extreme environment, with its limited flora and fauna, provides a unique opportunity to study survival strategies of organisms in extreme conditions, further enhancing our understanding of the potential for life on other planets.

Haughton Mars Project (HMP)

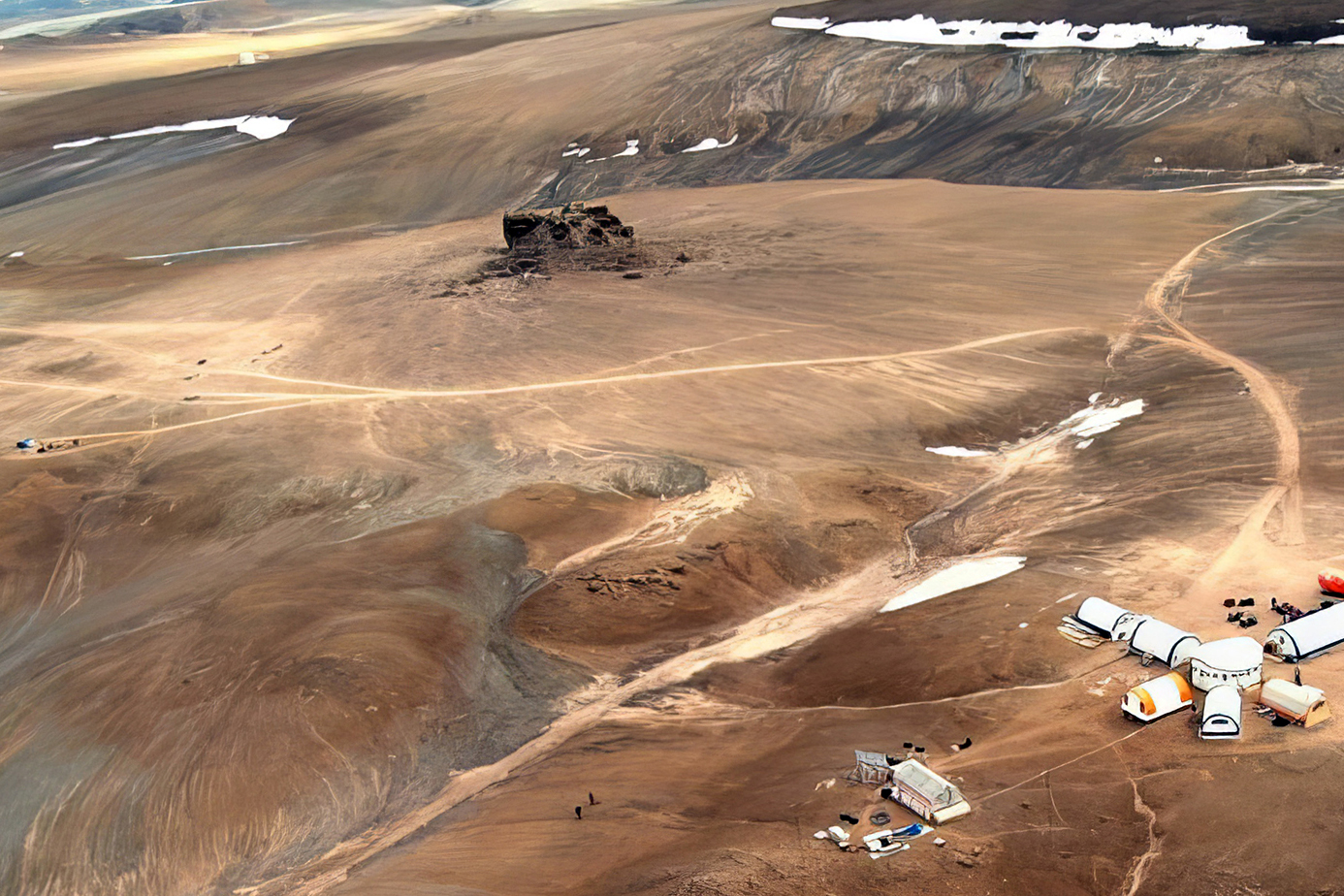

The Haughton Mars Project (HMP) is an international multidisciplinary field research project centered around the Haughton impact crater on Devon Island, High Arctic, Canada. This location is particularly significant due to its Mars-like conditions, including extreme environmental features, a cold climate, and a unique geological landscape. The project, operational since the 1990s, is designed to advance our understanding of the Martian environment and to develop key technologies and strategies for future human and robotic exploration of Mars.

Researchers and scientists involved in the HMP explore a wide range of scientific questions related to planetary science, astrobiology, environmental science, and more. They utilize the Haughton crater and its surroundings as analogs for the Martian surface to study processes that could be occurring on Mars. This includes investigating the biology of extremophiles—organisms that thrive in extreme conditions—geological formations similar to those found on Mars, and the impact of meteorites on planetary surfaces. The project also serves as a valuable test bed for developing and testing equipment, habitat designs, life support systems, and operational procedures intended for future Mars missions. Through its comprehensive approach combining field research with technology development, the HMP contributes significantly to preparing humanity for the challenges of interplanetary exploration.

Radstock Bay and Caswell Tower

Radstock Bay, located on the western side of Devon Island, is notably marked by Caswell Tower's striking cliffs, a prominent and solitary peak. This area is critically important for polar bear dens, observed from a small observation hut perched at the peak, which offers sweeping views of Radstock Bay and the distant Lancaster Sound. The elevation reveals the ancient coastlines, elevated beaches that trace back to the landscape's gradual ascent from the last Ice Age's weight. Near the foot of Caswell Tower, visitors can discover archeological remnants of Thule culture dwellings, identifiable by their whalebone roof structures, and 90 million-year-old fossils.

In conditions reminiscent of a challenging Arctic "summer," our journey to shore via Zodiacs was met with near-freezing temperatures, strong winds, and a mix of drizzle, sleet, and snow. This inclement weather provided a real sense of the historical expeditions that sought the Northwest Passage, including the harrowing experiences of the Franklin expedition's 129 members, who faced overwintering hardships nearby. The graves of three sailors from the winter of 1845-1846 on Beechey Island underscore the perilous conditions endured by early explorers.

Flora and Fauna

Devon Island's harsh and remote Arctic environment is home to a sparse but resilient variety of flora and fauna, adapted to survive under extreme conditions. The vegetation is limited, primarily consisting of mosses, lichens, and a few hardy species of Arctic wildflowers that manage to thrive during the brief summer months when the ice retreats. These plants form a critical component of the island's ecosystem, supporting the limited but diverse wildlife that inhabits the area. Despite the barren landscape, these pockets of vegetation are vital oases for the island's animal inhabitants, offering nourishment and shelter amidst the desolation.

The fauna of Devon Island is characteristic of the High Arctic, with polar bears being one of the most iconic and significant species present. These apex predators are often found near the coast, hunting for seals, their primary food source. In addition to polar bears, the island supports populations of Arctic foxes, which scavenge and hunt smaller prey, and migratory bird species, including snow geese, peregrine falcons, and loons, that arrive in the summer to nest and feed in the relatively untouched wilderness. The presence of these birds adds a burst of life and activity to the otherwise silent and stark landscape, highlighting the interconnectedness of ecosystems even in the planet's most inhospitable regions.

Devon Island stands as a testament to the importance of Arctic research and its role in advancing our understanding of extreme environments and space exploration.